“Hey, whatever happened to the tapes you made when I was high?”

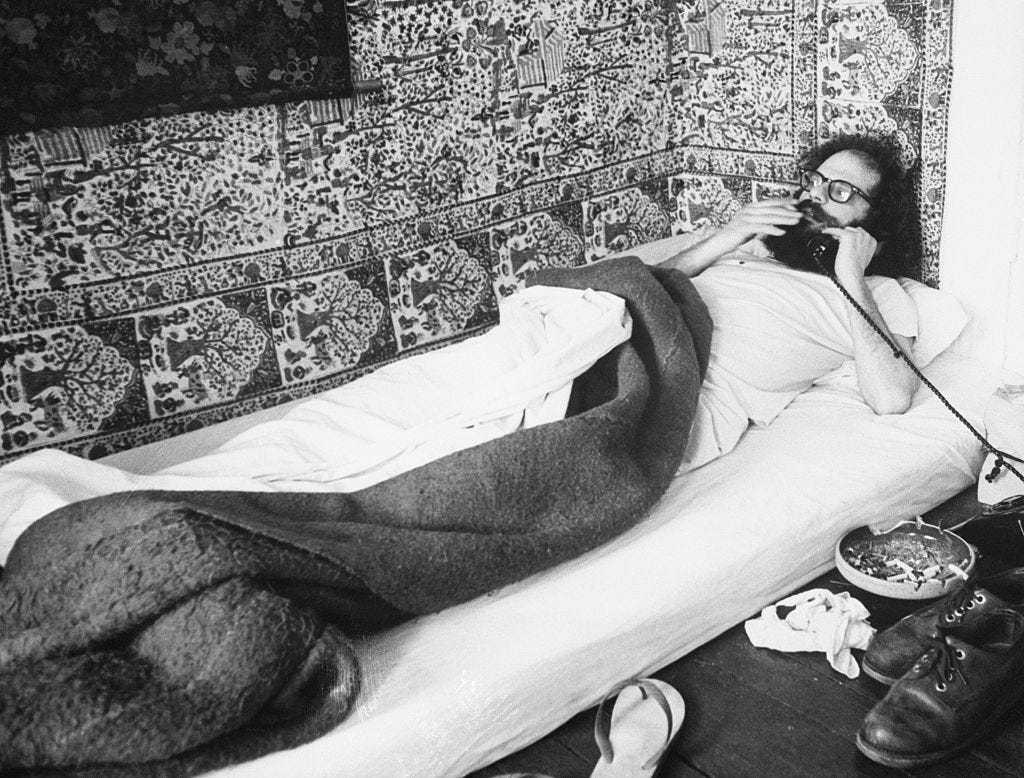

The poet Allen Ginsberg and an old reel-to-reel tape recording found in the Stanford archives.

Below you’ll find an excerpt of my book Tripping on Utopia: Margaret Mead, the Cold War, and the Troubled Birth of Psychedelic Science about the origins of psychedelic science in 1930s through 1960s. By drawing on understudied archives and original interviews, it restores key players in the field's origin — many of them women — to their rightful place alongside more familiar names like Timothy Leary. (The New Yorker's recent review of the book does a wonderful job summarizing the overall argument). This excerpt captures a crucial moment of transition as psychedelics begin their march toward illegality. The key historical source here is a tape recording made by the poet Allen Ginsberg in which he speaks to a little-known pioneer of psychedelic therapy named Joe K. Adams. Working at Palo Alto's Mental Research Institute in 1959, Adams was the psychiatrist who oversaw Allen Ginsberg's first LSD trip. That year was, with hindsight, a pivotal one not just for both men, but for the history of psychedelics as a whole.

Excerpt from the chapter “Dialectics of Liberation”

It is the evening of December 12, 1965, and Allen Ginsberg is backstage during the intermission of Bob Dylan’s concert in San Jose, California. He is chatting with Dylan about Ginsberg’s new portable tape recorder. “It looks groovy,” says Dylan. “Is it worth it?”

“Oh yeah, it’s an absolutely beautiful precision machine,” Ginsberg boasts. “It can do anything.”

Dylan is close to the recorder, and the mic picks him up clearly as he contemplates the rotating wheels of magnetic tape. “I don’t know why the fuck I don’t get one of those,” he murmurs. A few minutes later, he and Ginsberg start gossiping about Marlon Brando.

Later that night, the same tape recorder captured another conversation— one between Ginsberg and Joe K. Adams, the Texas-born psychiatrist who had worked alongside Gregory Bateson and Don Jackson at Palo Alto’s Mental Research Institute. By this time, Adams had quit science. Secure in the Big Sur campground he now owned, he dedicated himself to baking whole wheat bread, maintaining his vacation cabins, and writing playful essays about sexuality, consciousness, and the harms of psychiatric care. He no longer saw himself as a mental health professional with a Stanford affiliation. Instead, he was part of the psychedelic counterculture. As a contributing editor of a new journal, the Psychedelic Review, Adams shared duties with fellow editors Timothy Leary, Richard Alpert, and Alan Watts. He was also a core member of the Esalen Institute community, leading seminars and mingling with the institute’s newly fashionable clientele. And, as happened to be the case on this night, hosting Allen Ginsberg and his lover, Peter Orlovsky, for a cup of tea.

On the tape, Adams has a friendly voice with a molasses-thick East Texas lilt. Ginsberg begins showing Adams his new gadget—how the recorder can be plugged into loudspeakers, radios, guitar amps, capturing everything like a roving electric consciousness. The thought brings Ginsberg back to six years earlier, to his first LSD trip at the MRI—the trip that inspired a poem called “Lysergic Acid” about feeling as if he were plugged into a vast electronic machine. The trip that Gregory Bateson had organized and Joe Adams had overseen.

“Hey, whatever happened to the tapes you made when I was high?” Ginsberg asks. “Was there anything interesting on them?”

“Well, I’m not sure if I have those tapes, or if they’re back at the Mental Research Institute,” Adams replies. “I would have to go through all my tapes and see.”

They move on to other topics. But Ginsberg keeps circling back to the events of 1959 and 1960. At the poet’s prompting, Adams recounts his catastrophic LSD trip, the one that contributed to the fracturing of the Mental Research Institute. “It was in January [1960] when I had my reaction,” he remembers. “And I was high. For. Months...I was really crazy. I took my clothes off and started runnin’ around the driveway.”

“Here?” Ginsberg asks.

“No, no, nooo...it was in Menlo Park!” Adams says to sympathetic laughter from Ginsberg and Orlovsky. “A nice, suburban neighborhood. And I was intercepted by a psychiatrist in the driveway. My wife had called them.” His voice is amused and detached, as if he’s describing a scene from a play. “Three uniformed men came and tied me down on a stretcher and took me to the mental hospital.” In his delusional state, Adams found himself dwelling on mass manipulation, psychological warfare, and World War II. “I realized how horrible this was,” he explained, apparently referring to his experience of psychiatry during the 1940s and 1950s. He concluded that he was trapped in a sinister Cold War plot: “I tried to escape there and ran out and climbed over a fence and I yelled, ‘This is not a hospital!’...You see, there were two shifts of aides, and I thought there was a U.S. shift and a Russian shift. I thought it was a big experiment of some kind and I was a guinea pig. And the whole place—I thought the whole place had microphones in it. And, oh, well...it was very complex.”

“What led you up to that?” Ginsberg asks, fascinated. “You know, very oddly, the first time I had LSD with you, I suspected that you were a Russian agent, a Russian spy. Remember that? Remember I mentioned that I thought it was a Russian plot? I knew it was involved in the Cold War somehow.”

Adams laughs warmly. “No, no, I don’t remember that,” he says. “That’s . . . uh . . . huh.” He doesn’t elaborate further.

The two men had been brought together by Gregory Bateson at the end of the 1950s, during the height of psychedelic science’s cultural prestige. Adams had once been a true believer. Ginsberg, in a sense, still was. It was this shared utopian sensibility, this deep idealism, that sparked their friendship.

When Ginsberg labeled the tape of his conversation with Adams, he gave it an ironic title: “Acid Test.” One of the first acid tests—the name Ken Kesey and his followers gave to their parties—was in fact happening about three hours’ drive north of Adams’s cabin at the moment that they were discussing the strange events at the Mental Research Institute. Ginsberg’s name was even on the poster. But he didn’t show. Far more than his peers in the emerging psychedelic counterculture, Ginsberg was intrigued by the scientists, not the partiers. More than anyone else in the world in 1965, perhaps, Ginsberg was uniquely placed to understand the worlds both of psychedelic science and of the psychedelic counterculture. But as the winter of 1965 became the spring and summer of 1966, the poet grew increasingly disquieted by both worlds. He could not shake his sense that, as he put it, the psychedelic experiments at the MRI and elsewhere “had something to do with the Cold War.” And he also believed that the new American messiahs of psychedelic spirituality were getting something fundamentally wrong.

Psychedelic science had always been a global project, winning adherents in places like Prague, Zurich, London, and even Baghdad years before it reached relative latecomers like Ken Kesey and Timothy Leary. The psychedelic counter-culture was, at least at first, no less global. In Brazil, artist Hélio Oiticica created overtly “trippy” interactive artworks, inspiring a generation-defining cultural movement known as Tropicália. In Santiago, Chile, a young physician named Claudio Naranjo returned from a Fulbright scholarship at Harvard, where he took mushrooms with Frank Barron, believing psychedelics were tools for “a collective transformation of consciousness.” And ancient psychedelic traditions, such as the use of ayahuasca, a potion made from two Amazonian jungle plants, found new followers amid rapid urbanization across the Amazon basin.

Stateside, however, the vivid diversity of global psychedelic culture was becoming monochrome in a distinctly midcentury American way. Mead had long called for a truly diverse and broad-based global cultural change. Yet while the psychedelic counterculture embraced “non-Western spirituality,” it did so in a superficial and romanticized way that did not truly challenge Western cultural norms. Tom Wolfe memorably described Stewart Brand (who drives the Merry Pranksters’ bus through the opening pages of The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test) as wearing “just an Indian bead necktie on bare skin and a white butcher’s coat with medals from the King of Sweden on it.” Underneath the costumes, however, were bodies that were almost invariably American, white, middle class, and male. And in the new psychedelic spaces that emerged across the United States, from Esalen to Greenwich Village, it did not take long for all the usual ills of twentieth-century American life—alcoholism, political polarization, racism, greed—to reassert themselves.

“We are seeing accidents happen,” Sidney Cohen lamented in March 1966. “We are frightening the public. We are getting laws passed [banning the drug]. We are not using the anthropological approach of insinuating a valuable drug of this sort into our culture” by “gradually demonstrating the goodness of the thing.” For Cohen, “the anthropological approach” meant a science built on and with the cultural patterns of other societies, not an attempt to invent them from scratch—Margaret Mead’s approach, in other words. But now, Cohen complained, the anthropological approach to drugs was being abandoned in favor of reckless experimentation—“these Acid Tests that go on with these bizarre individuals.”

A few weeks later, on May 24, 1966, Senator Robert F. Kennedy sat down at a large table in the New Senate Office Building to convene a congressional investigation of LSD. “Here is a drug which has been available for well over 20 years,” the senator said. “Yet suddenly, almost overnight, irresponsible and unsupervised use of LSD for nonscientific, nonmedical purposes has risen markedly.” The dangers had, too. Kennedy feared that “without careful psychological screening, the drug will be used by some who suffer permanent damage as a result.” In other words, “what was an experimental drug has become a social problem.”

Given the decades of prohibition that began later—decades in which LSD and other psychedelic drugs would be lumped together with heroin as Schedule 1 drugs of abuse, and tens of thousands would spend years in jail for possession of psychedelic drugs—it is tempting to see Robert F. Kennedy’s statement as an early salvo of what Richard Nixon, five years later, would label the “war on drugs.” But 1966 was not 1971, and the future was not yet written. Senator Kennedy concluded his opening statement by describing the benefits of psychedelic therapy. “Experiments indicate that LSD may be useful in treating alcoholics—one of the largest groups of the handicapped,” noted the man whose own family struggled with addiction. The “loss to the Nation if LSD were to be banned,” Kennedy warned, “would be serious indeed.”

This balanced tone was, however, already being drowned out by polarized commentary from both sides. In a parallel series of Senate hearings held the same month, a succession of narcotics officers and antidrug doctors shared horror stories about trips gone wrong. A jarring note of positivity came amid the scaremongering when one narcotics detective quoted an interview with Cary Grant in which the Hollywood actor credited LSD with improving his life and allowing him to “truly give a woman love for the first time.” The thought seemed to disconcert one of the senators present, Thomas Dodd of Connecticut. “I think in fairness to Cary Grant,” Senator Dodd ventured, “we do not know that he ever said any such thing.” The detective agreed. The point he was making, he reassured the senator, was simply that the media was lying about psychedelics in such a way as to make the drug “attractive to our teenagers and our youth of today.”

Allen Ginsberg spoke at the hearings, too. But the bearded poet did not exactly inspire confidence. “I don’t think it is necessarily frightful or dangerous. It could be dangerous if we react dangerously to it,” he told the senators. “But it is very hard to say yes, let the high school kids get it, because it scares everybody. The problem is not to scare everybody.” Ginsberg tried to cite the members of the Macy circle as illustrious proponents of psychedelic therapy, but the details eluded him (Ginsberg cited the research of “Dr. Harold Abramson of New York, who is a very considerable figure, the head of some hospital or other”).

And, worst of all, he lumped these distinguished scientists in with Timothy Leary. Because, when Leary himself rose to speak, the ex–Harvard lecturer informed the subcommittee that “the so-called peril of LSD resides precisely in its eerie power to release ancient, wise, and I would even say at times holy sources of energy which reside inside the human brain.” Under its influence, he added, “you definitely go out of your mind, there is no question of that. To some people this is ominous.” Leary’s remarks were widely quoted and misquoted in newspapers.

The senators were unimpressed. “I am trying to follow the best I possibly can,” Robert F. Kennedy said to Leary, interrupting his rambling testimony. “And I find that I am completely unable to do so.”

By November, even Allen Ginsberg felt disenchanted. In a speech in Boston that month, he encouraged his audience to “try the chemical LSD at least once.” But he also expressed fear of a “chemical dictatorship”—an allusion to the era’s ever-present fear of brainwashing and mass mind control—and urged those in attendance not to assume that psychedelics were a solution for anything. They were simply one way of understanding the problem: “anger and control of anger.”

Please note there will be no This Week In Psychedelics news post on Friday, March 15. We will be back in your inbox with another 5 Questions on Monday, March 18.