It’s Friday afternoon, and these two reporters are exhausted from three whirlwind days at Psychedelic Science 25. We’re not the only ones — many attendees we’ve spoken with have noted a subdued energy and a general sense of malaise. While many leaders delivered hopeful messages, the event felt smaller and less energetic than it did in 2023: a few hours before the closing plenary, conference organizers announced the talk would be moved from a 5,000-capacity venue where the opening plenary was held to a smaller ballroom.

Another journalist remarked to me that while the conference’s theme was “The Integration,” it might be more fitting to call it “The Comedown.” After the highs of 2023, many of the panels centered around taking a sober look at the state of the psychedelics field, and how to move forward. Several had the phrase “lessons learned” in the title, including a panel I moderated Wednesday about failed psychedelic start-ups, in which Field Trip founder Ronan Levy and Journey Colab founder Jeeshan Chowdhury took the “realist” view: that growing too quickly and raising too much capital has its drawbacks, and that well-intentioned equity initiatives are viewed by investors as “additional complications” to a business. As the field matures, these panels show an acknowledgement of missteps over the years.

In a panel yesterday on state-regulated psychedelic legislation, attorney Allison Hoots mentioned that psychedelics’ illegality contributes to its overall risk, because people using them outside of legal contexts are often reluctant to report abuse and misconduct, and have no established outlets to do so. On a panel called “Sacramental Churches Today: Obstacles, Opportunities, and the importance of self-regulation,” Hoots, who is also the executive director of the Sacred Plant Alliance (SPA), discussed the group’s goal to become a consortium of psychedelic churches to create more accountability— and to advocate for churches’ rights. SPA announced last week that they plan to sue the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration in civil court for taking too long to review churches’ petitions to receive exemptions from the Controlled Substances Act to use psychedelics as sacraments in their churches. “We had a meeting with the DEA and expressed concerns about the petition process about a year ago, and nothing happened,” Hoots said. “We also sent a letter about two months ago saying we have a real problem — their administrative process does not work.”

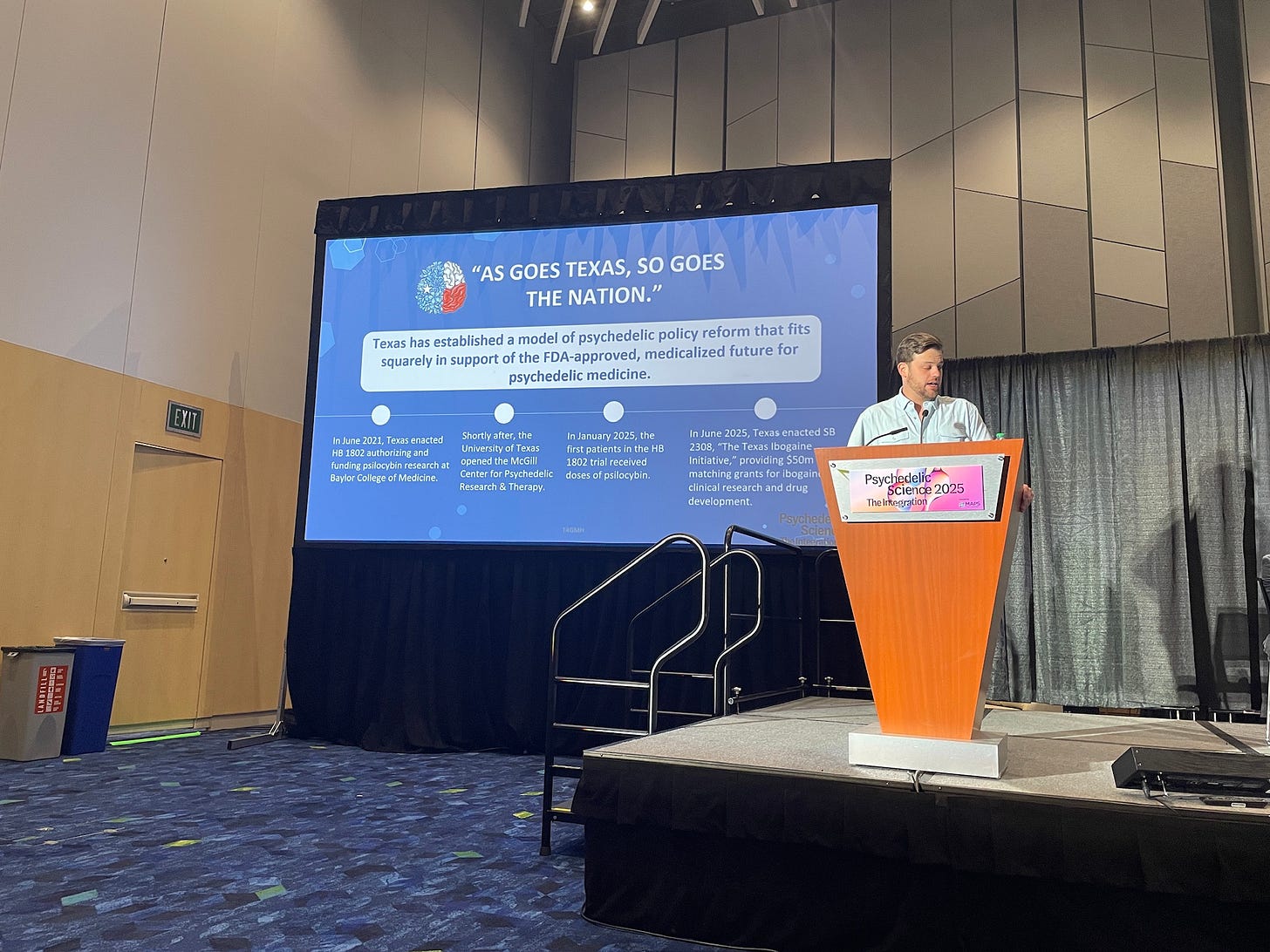

Advocates from Texas, Nevada, Minnesota, and New Mexico spoke about their state’s psychedelic legislation in “Alternate State Models: Beyond Colorado and Oregon.” All four spoke of the importance of coalition building between researchers, veterans, and legislators. Logan Davidson, Executive Director of Texans for Greater Mental Health, said it was important to his state’s success in passing ibogaine legislation to have a “tightly controlled narrative,” where they platformed special operations veterans and victims of opioid epidemic, and trained them on talking points. “That way, if a legislator talks to me one day and Marcus Capone the next, there’s no opportunity for confusion,” Davidson said. Capone is a Navy SEAL veteran and co-founder of the non-profit psychedelic advocacy for veterans group VETS.

Tourists are flocking to Latin America for psychedelics retreats and ceremonies, and on the panel “Sacred or Stolen? The Fine Line Between Cultural Appreciation and Appropriation in Psychedelic Healing,” Brazilian historian Lígia Duque Platero said that the line may be where non-Indigenous people profit from Indigenous knowledge. Some are selling medicines or learning how to make Indigenous bracelets and necklaces and selling them — and their profits are not shared with the Indigenous communities they learned from. Mazatec historian Osiris García Cerqueda asked the audience how many people in the audience were Mazatec — no one raised their hands. But when he asked how many people have used psilocybin, most of the room put their hands up. “Ah, and you are not Mazatec,” he said. “Since 70 years ago, Mazatec people have shared this knowledge with you. Many of the families in Mazatec territory don’t have any problem with you taking the mushrooms, but the big issue is when foreigners try to sell these mushrooms with the image of Maria Sabina, and the narrative of Mazatec people.”

In a panel called “Ketamine Reality Check: Miracle, Mirage, or Misused?” podcaster Hamilton Morris and psychiatrist and president of the Center for Natural Intelligence Gita Vaid seemed to land in a much more neutral territory than any of the options in that alliterative string of words. “Most of the negative effects of ketamine can be prevented by moderate consumption,” said Morris. Vaid, who works with ketamine in her practice and described the experiences of several clients, said ketamine “could be magical” at higher doses but she stressed her discomfort with mail order ketamine and ketamine taken without the container of psychiatric support. They briefly touched on high profile ketamine news stories, namely the death of actor Matthew Perry and the recent New York Times piece claiming that Elon Musk, “told people he was taking so much ketamine, a powerful anesthetic, that it was affecting his bladder.” “I’ve always had a laissez-faire attitude about other people’s drug use,” said Morris. “When it comes to widespread access I’m broadly in favor as long as people can agree that they understand the risks.”

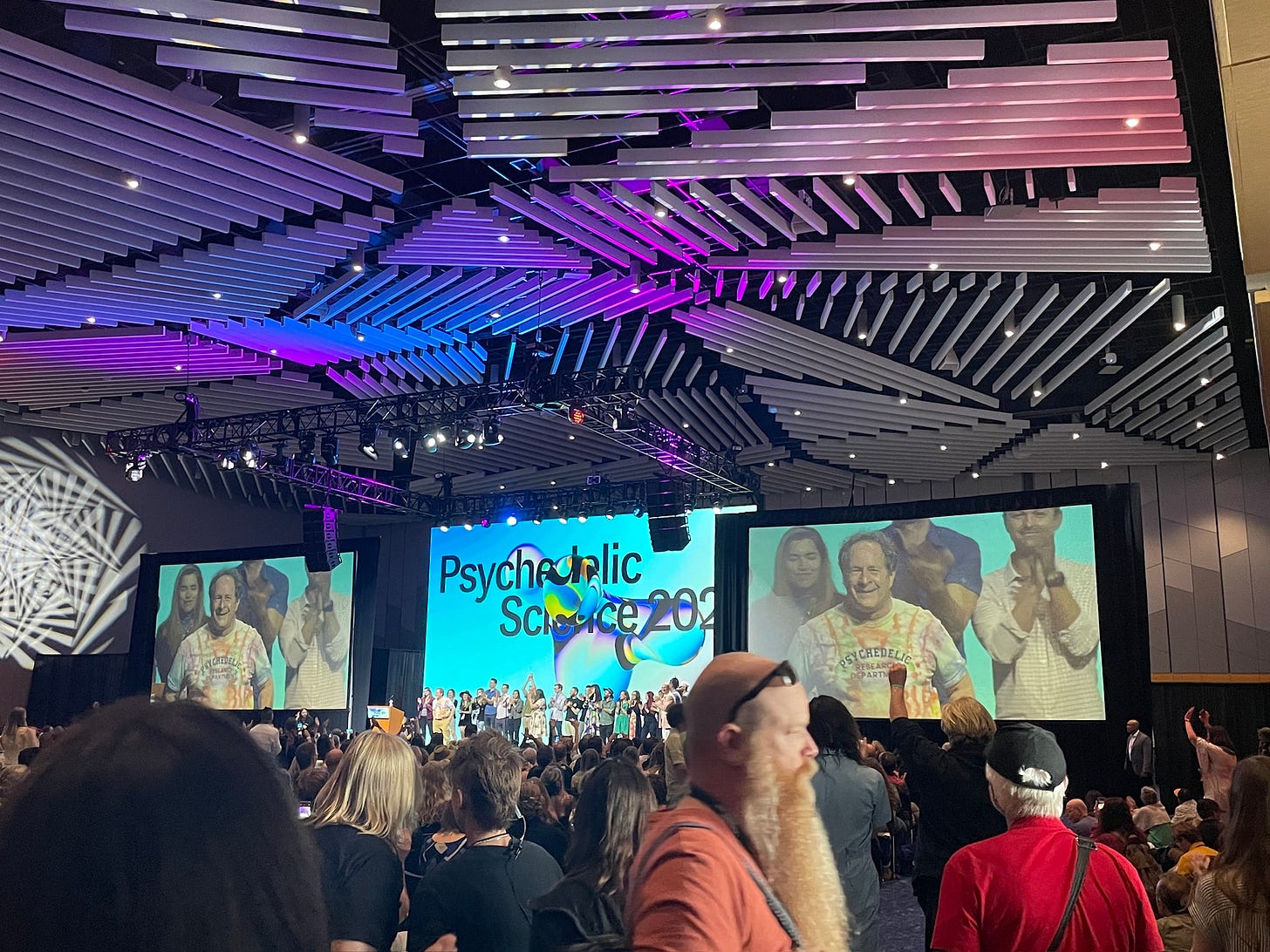

Outside the closing plenary, long lines snaked outside the Bluebird ballroom as attendees lamented whether they would ever be able to get in. According to a building manager, the room had around 1,050 chairs set up, though there were also attendees sitting on the ground, and others waiting outside. On Wednesday morning, the MAPS media team told me they were expecting between 8,000 and 10,000 people, but even accounting for people who left the conference early and did not attend the plenary, that estimate seems high. Speakers like University of Washington researcher Anthony Back, drug educator Rhana Hashemi, and the Indigenous Peyote Conservation Initiative’s Sandor Iron Rope reflected on their experiences at the conference, and offered messages of hope, and MAPS interim co-directors Ismail Ali and Betty Aldworth brought MAPS staff on stage. “Oh wait, did we forget someone?” Aldworth said, as the crowd began chanting “Rick! Rick!” Rick Doblin appeared on stage to a standing ovation wearing a tie-eyed MAPS t-shirt that read “Psychedelic Research Department."

“It’s been a long enough time after the disasters of the FDA and Massachusetts initiative — after the defeats — that we’ve had enough time to process it, learn lessons, and see how to go forward,” Doblin said. “I wasn’t sure what this conference would be like until we got here - that it would be about hope and what to do in the future. There’s this sense that we need each other but there will be a lot of opportunities for growth, it will continue.”

And that’s a wrap! Thanks for joining us for our updates from Psychedelic Science 2025, and thanks to the readers who took the time to come say hello at the conference. We’ll be back in your inbox on Monday with another issue of 5 Questions.