Not everything’s bigger in Texas

I went to SXSW and learned about “the mullet” approach to psychedelics

“Oh, I’ve seen a few of you psychedelics people come through,” the volunteer at South by Southwest’s check-in told me as he printed out my panelist badge. “Bunch of guys with big beards — really looked the part.” Last weekend, the annual arts, music and technology festival South by Southwest descended upon downtown Austin; this was the third year the conference included a psychedelics track.

Austin offered an interesting backdrop for a psychedelics conference. The city is a blue dot in an otherwise red state, and in recent years, has transformed into a new epicenter for technologists, many of whom have decamped from California. Some of the most prominent, politically conservative psychedelics advocates these days reside, at least some of the time, here in Texas. Joe Rogan and Elon Musk both have houses in the Austin area; Musk had plans to build Snailbrook, a company town for employees of SpaceX and The Boring Company, in the Austin suburbs. Alongside the psychedelics track, there was also a “2050 track” sponsored by Dubai Future Foundation with talks from the likes of longevity fanatic and entrepreneur Bryan Johnson and Bluesky CEO Jay Graber.

Texas is also taking steps towards becoming a leader in psychedelics advocacy. In 2021, the state became one of the first to fund a clinical trial investigating the use of psilocybin in treating veterans with PTSD. Several psychedelic access legislative efforts followed. Right-leaning figures like Rick Perry, the former Texas governor and Secretary of Energy in the first Trump term have become psychedelic advocates on the national stage.

After badge pick-up, I made my way to the second floor of the JW Marriott, where the psychedelics track was to be held. The two-block walk took me past throngs of badge-clad attendees, and a two-story tall gold chalice advertising the Netflix show “Love Is Blind.” Around another corner, a line of people snaked nearly a full block before entering the Texas-based fast food chain Whataburger’s Museum of Art. At the Marriott, people from other SXSW tracks — design, food, advertising and brand experience — milled about the lobby and the hotel Starbucks. The psychedelics track was on the second floor, relegated to two staid hotel conference rooms.

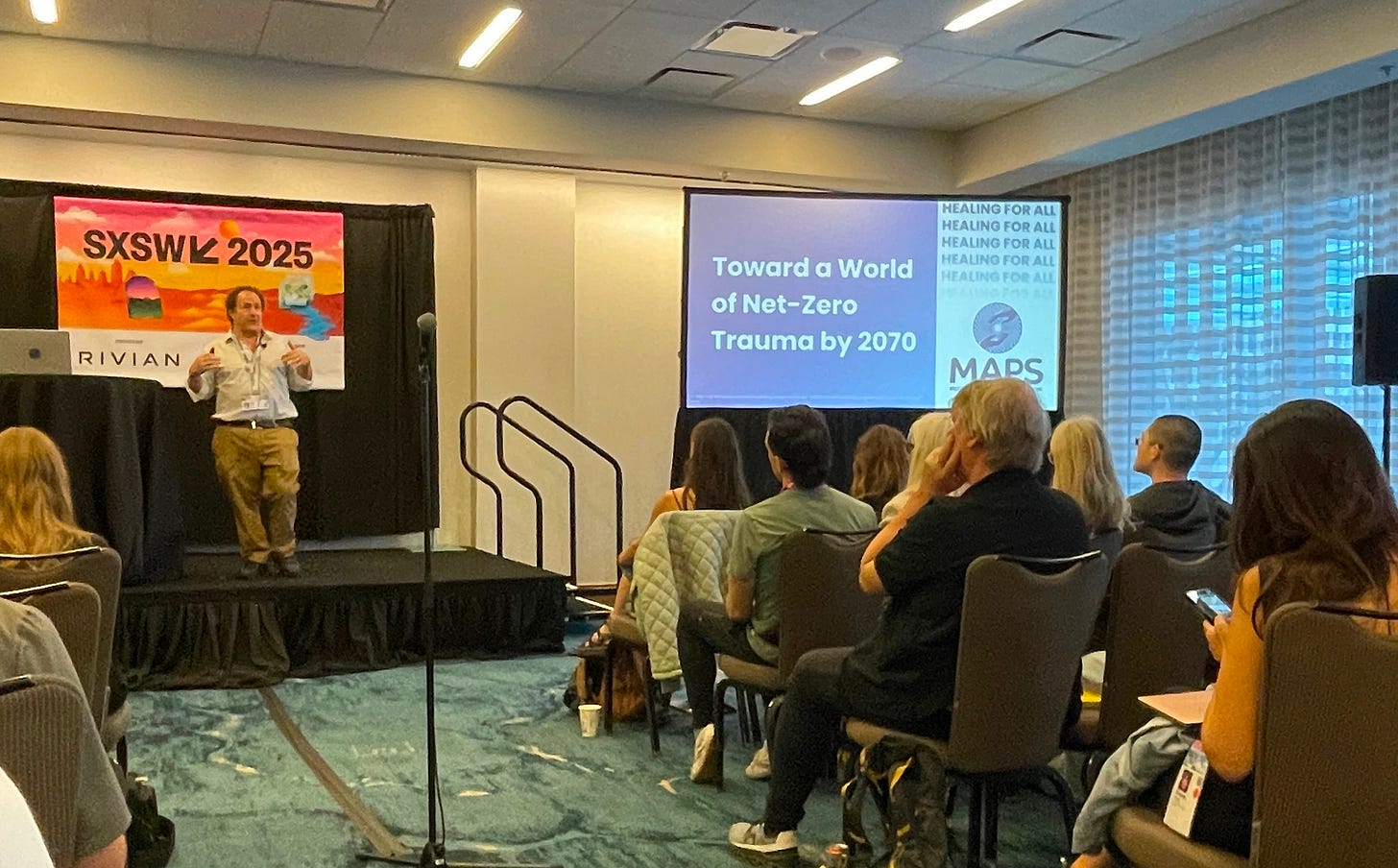

I arrived just in time to see MAPS founder Rick Doblin give a talk called “MDMA-Assisted Therapy: Going to the Trauma, Not the Profits.” The last time I saw Doblin speak was in Denver at MAPS’ conference, Psychedelic Science, in 2023; he took the stage there wearing an all white suit and was cheered on by a crowd of thousands. At the time, I wrote that Doblin wandered the stage looking and sounding like a preacher. A woman sitting next to me was so moved, she wept.

But Doblin’s talk at SXSW had little of that zeal and enthusiasm. I was surprised that there were just a couple dozen people in the audience. This time, Doblin wore khakis. That shift made sense to me, given the seismic changes in the psychedelics industry since Doblin’s explosive Denver talk. Last summer, the FDA rejected Lykos Therapeutics’ application to use MDMA-assisted therapy in treating PTSD, and requested the company conduct new clinical trials. After that, the company laid off 75% of its workforce and Doblin stepped down from the Lykos board.

During his talk in Austin, Doblin explicitly distanced MAPS from Lykos, calling out Lykos’s missteps in the FDA application process several times. But Doblin seemed hopeful for Lykos’s future, and confirmed that he had brokered a recent deal where billionaires Antonio Gracias and British hedge fund manager Christopher Hohn will become majority owners of the company. He said Gracias and Hohn were committed to reinvesting any profits they make back in the company, and in particular, bringing MDMA-assisted therapy to “India and Africa.” Doblin called them “investors focused on using resources not for personal gain but healing the world.”

Doblin also mentioned that the FDA had assigned Lykos’s MDMA application independent third party reviewers, whose review of the clinical trials’ data will determine what happens next with the Lykos’s application, calling it a “proverbial fork in the road.” The reviewers could, Doblin said, determine the trials’ data is reliable: “MDMA could be approved in six months or so without an additional Phase 3 study. That's the best option,” Doblin said. Lykos has already publicly discussed the other option, which is that the FDA will ask for the company to run another Phase 3 clinical trial, a process Doblin estimated would take another three years.

Doblin returned to some of the big-picture ideas he’s been talking about for years, such as psychedelics as a tool to achieve what he calls “net-zero trauma.” He also noted his interest in using psychedelic therapies for applications that won’t result in royalties or profits. “The FDA has only approved drugs for conditions in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM),” Doblin said, so Lykos would not be able to submit applications to use the drug for things like couples therapy, which is not in the DSM. He also referenced Stanislav Grof, a Czech psychoanalyst whose ideas were fundamental to MAPS’ MDMA therapy manual and who says the “future of psychiatry is to take MDMA and then an hour later, five MeO-DMT.” Underground therapists, Doblin said, are already combining MDMA, psilocybin, and LSD in treatments and “are the real heroes of this whole movement and they are years ahead of what's happening in research.”

Other presentations over the three days included a panel on the social justice promises of psychedelics decriminalization, another on using states’ opioid settlement money to fund ibogaine research, and another on the future of PTSD treatment. The majority of the two dozen other talks were heavy on the advocacy, with people sharing intimate stories of healing or how psychedelics changed their lives. Some even had big pep rally energy. “Who microdosed today?!” one speaker shouted into the audience before his panel on psychedelics in the media began.

Many talks presented optimistic views of what the psychedelics world could become, discussing strategies that can help bring psychedelics even more into the mainstream. For example, in a panel about employers offering psychedelics as a mental health benefit, one panelist suggested potential psychedelic-assisted therapy providers should professionalize themselves using the “mullet approach”: business up front, party in the back. “If it feels safe, then we can make it more mainstream for more people,” said another panelist, Lee Lewis, who is the chief strategy officer at Health Transformation Alliance, a cooperative of 70 companies including Shell, Kaiser Permanente, and Walgreens that share resources with one another to bring down healthcare costs for their employees. Sherry Rais, co-founder and CEO at Enthea, a company that administers third-party mental health plans that include psychedelic therapy, said that when she was first pitching Enthea’s services to companies, using the term “psychedelic therapy” didn’t get many hits, but she’d recently found more success using more general language framed around mental health. “We've grown a lot because now we just don't say psychedelics, we don't say ketamine. We just say, ‘Do you want innovative mental health treatments? Do you want disruptive mental health treatments? Do you want transformative mental health treatments?’ It's the same thing we're offering, but that language helps a lot,” said Rais.

In a panel on churches that use psychedelics as religious sacraments, attorney Sean McAllister discussed how to widen access to psychedelics through leveraging religious freedom protections. Under the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof. ” In other words, the constitution enshrines all kinds of rights to religion. “What they say when you fight an opponent is you shouldn't attack your opponent's weakness, you should attack their strength. And this is what the psychedelic movement has done,” he said. “Because of the strength of religious freedom in the United States, then we ask the government to recognize this value that it says it cares about so deeply.”

I participated in a panel called “Behind the Scenes of the ‘Psychedelic Renaissance,’” where Psychedelic Alpha’s Josh Hardman, Calyx Law’s Graham Pechenik, The Atlantic journalist Shayla Love and I had a wide-ranging discussion about the last five years in the psychedelics field. We talked about how companies’ approaches to patents have changed, the importance of rigorous journalism to the emerging psychedelics field, what the Trump administration could mean for psychedelics, and our predictions for the next five years.

People who had attended previous psychedelics tracks at SXSW told me this year felt sleepier and smaller than the previous two years, when enthusiasm about psychedelics entering mainstream medicine was perhaps higher. I was told that in 2023 and 2024, there were lavish parties thrown by moneyed sponsors, while this year’s after-hours offerings were fundraisers for organizations like MAPS or required paid tickets for attendance. I talked to several people who were actively looking for work after being laid off from psychedelics-related companies or organizations, or were planning how to pivot their work away from psychedelics as a safety net in case the industry contracts.

While things were sleepier, they weren’t lethargic. The relative physical isolation of the psychedelics track from the rest of the conference resulted in an insider-y group, where people really cut loose at the after parties, and the gossip mill churned fast and hot: Who had which drugs? Who was tripping together? Who was dating? Why did people leave or start jobs? Common side conversations topics included people’s recent psychedelic experiences, and their hopes and fears for the new administration. Even some right-leaning attendees expressed trepidation about whether enthusiasm for psychedelics from leaders like Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and Elon Musk would actually translate to a more favorable political environment for these substances or a faster track to their approval by the Food and Drug Administration.

During Doblin’s talk, he spoke about the mood at that MAPS conference in Denver back in 2023: “That was a time of exuberance and hope,” he said wistfully, trailing off. That unfinished sentence felt like the theme of the weekend: a yearning for the past, a time when the outlook for psychedelics felt easier — rosy, even.