Psilocybin and SSRIs perform similarly six months after treatment; Oregon psilocybin program proposes revised rules; DEA increases quotas for psilocybin and psilocin

Plus: Surveying the underground, and understanding mescaline

Happy Friday and welcome back to The Microdose, an independent journalism newsletter brought to you by the U.C. Berkeley Center for the Science of Psychedelics.

Psilocybin and SSRIs perform similarly six months after treatment

As researchers study the potential of psychedelic-assisted therapy (PAT) in treating depression, many people have been hopeful that psychedelics will be more effective than current treatments, particularly selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). While PAT has produced promising results for participants in the days and weeks after treatment, few studies have followed patients and examined effects months later. But a study published recently in The Lancet’s journal eClinicalMedicine does just that, following up with participants in a psilocybin study six months later.

The original study, which was published in 2021, made a big splash. The Imperial College London researchers gave 59 patients with major depressive disorder either two psilocybin doses or a more conventional treatment (a course of the SSRI escitalopram over a six-week period). Researchers measured changes in participants’ depression scores as their primary measure. Immediately after the study, both groups showed reduced depression symptoms but, on the primary outcome measure, there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups. (On some secondary measures, psilocybin treatment outperformed escitalopram.) In the 6-month follow-up study, both groups continued to show improvements in their depression symptoms, but there was no significant difference between the two groups.

Participants in the new study also filled out questionnaires measuring how they function socially and at work, how they felt about their sense of purpose and meaning in life, and how connected they feel to others. Participants in the psilocybin-assisted therapy condition reported greater improvements in those areas. “These are crucial aspects of recovery that go beyond symptom reduction, indicating that PAT may foster more holistic mental health benefits,” Imperial College researcher Tommaso Barba, the paper’s corresponding author, wrote on X.

Interpretation of these results depends on your perspective on SSRIs. If psilocybin-assisted therapy performs similarly to available antidepressants, that suggests it’s at least as effective as existing treatments. And given that 34% of patients in the SSRI condition continued taking the medication after the initial 6-week session or resumed taking it in the 6 months after, it’s hard to know how much of an effect the treatment had on the 6-month follow-up results. (The author hypothesizes that this sustained rate of response could be due to the “trial's intensive psychological support,” since SSRIs are not always paired with therapy.)

But for people hoping for a solution that outperforms current treatments, these results may not be inspiring — and in any case, it would be premature to draw conclusions from this study even though it is “tempting,” write researchers at Sweden’s Karolinska Institutet in commentary published in The Conversation. More studies with larger sample sizes are needed. But, they write, the study is a good step in the direction for the field, which should include longer-term effects. “Monitoring the duration of the effect of psilocybin for a minimum of 12 weeks, but ideally up to a year, has also been indicated as an important consideration for clinical investigation into the effectiveness of psychedelic drugs by the US Food and Drug Administration,” they note.

Oregon psilocybin program proposes revised rules

Now entering its third year, Oregon Psilocybin Services (OPS) has proposed revised rules for the state’s program. The changes, detailed in a 92-page document, reflect a maturing system. These new proposed rules set standards for what psilocybin businesses and facilitators need to do when closing a licensed business. There are also amendments made to reflect changes and issues the program has encountered over its first 15 months of operation. Some highlights:

Originally, OPS-issued licenses were good for 5 years; starting in 2025, new licenses will be valid for one year, and facilitators will need to complete four hours of continuing education before renewing licenses.

The rules have been amended to clarify details of service centers’ collection of data from clients, which was dictated by the Oregon legislature when they passed Senate Bill 303 in June 2023. Last year’s debate over SB303 was heated; while some lawmakers felt that collecting de-identified and aggregated data was necessary for monitoring the equity and safety of the state’s programs, others worried that it placed an undue burden on service centers to collect data, or that it could compromise the privacy of clients. In the end, the new law allows clients to opt out from having their data collected – but the new proposed OPS rules specifies that people working at service centers are prohibited from encouraging clients to opt out, “or otherwise influencing a client’s responses to the form.”

The new rules clarify rules dictating the licensing and accreditation of facilitator training programs. Since OPS launched, at least one approved training program has been threatened with deauthorization, and another one abruptly folded.

Measure 109, the ballot initiative that created OPS, dictated that for the first two years of the program, business owners seeking licensure with OPS had to demonstrate they had been residents of Oregon for at least two years. Now, that rule is sunsetting.

Clients can now bring a support person to sessions, and the consent form they sign includes “long-term distress, worsening psychiatric symptoms and cardiovascular effects” in a list of side effects. (See OAR 33-333-5040, or pg. 60 of the state’s Notice of Rulemaking document, for the state’s informed consent language.)

OPS is accepting public comment on the new rules through October 21, and will hold three public hearings about the draft rules.

Want the latest psychedelics news? Subscribe! (It’s free!)

DEA increases quotas for psilocybin and psilocin

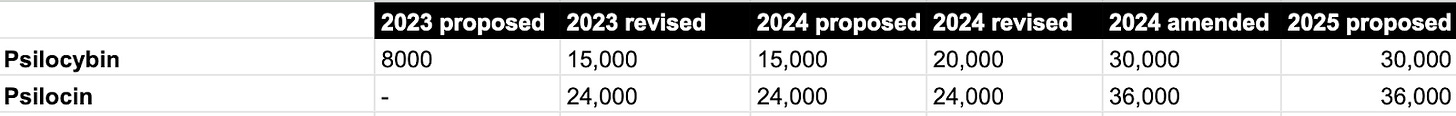

Each year, the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration publishes proposed quotas for the manufacture of scheduled drugs to be used in research. In a proposed change published to the Federal Register on September 25, the agency wrote that it wants to revise its 2024 quotas upward for psilocybin and psilocin. (When the human body breaks down psilocybin, psilocybin gets metabolized into psilocin.) “When the agency first proposed 2024 quotas in November 2023, the amounts it included were the same as its revised 2023 quotas, suggesting the agency expected the amounts of the drugs used in research to remain roughly the same,” the DEA wrote. Soon after, the agency revised those estimates upwards, and is proposing an even larger increase. They write that the changes “demonstrate DEA's support for research with schedule I controlled substances” and “reflect research and development needs as part of the process for seeking the FDA approval of new drug products.”

The DEA now proposes producing 30,000 grams of psilocybin and 36,000 grams of psilocin in 2024. The agency’s quotas for psilocybin and psilocin have steadily risen over the last couple of years; in late 2022, when the DEA proposed quotas for 2023, the agency allotted 8000 grams of psilocybin and no psilocin. That was revised upward to 15,000 grams of psilocybin and 24,000 grams of psilocin, and at the start of this calendar year, the DEA bumped the 2024 quota for psilocybin up to 20,000 grams.

In another document published on the Federal Register, the DEA also proposes psychedelic drug quotas for 2025 that are identical to those proposed in the amended 2024 quotas, with one exception: ibogaine. In 2024, the DEA’s quota for ibogaine was 150 grams; the DEA proposes an increase to 210 grams in 2025.

Surveying the underground

While Oregon has implemented a regulated program allowing supervised psilocybin sessions, and Colorado is close to launching a similar program, most psychedelic use still happens outside these state-regulated settings. A new study led by researchers at the University of Michigan surveyed over 100 underground psychedelic practitioners over the course of six weeks in 2023.

The results, published in The Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, suggest that most respondents screened participants for conditions that preclude the use of psychedelics, and around half charged for their services. The majority did not have therapy or counseling training and instead learned through experience or independent seminars and books. That could be a problem, the authors note: “Because unlicensed practitioners are not required to abide by state-wide standards surrounding professional training, continuing education, ethics, or legal protections, clients may incur additional risks when working with these individuals, such as ethical or personal boundary violations.”

Understanding mescaline

Mescaline — the psychoactive substance found in several cacti including peyote — has been used by Indigenous peoples for millenia. The resurgence of interest in psychedelics has also led to increased interest in mescaline; as peyote cacti have been overharvested, scientists have begun manufacturing mescaline in labs instead. Still, mescaline is among the lesser-studied psychedelics, and a new study, published in the journal Translational Psychiatry, set out to establish basic information about the drug, such as how it works in the body and the link between dose and participants’ experiences and physical effects. The study, led by researchers at the University of Basel in Switzerland, gave 16 people a placebo, or a 100, 200, 400, or 800 mg dose of mescaline. Overall, researchers found that the higher the dose, the more likely it was to induce visual alterations, feelings of happiness, and ego dissolution. The drug also increased blood pressure and heart rate, and at the highest dose, frequently caused nausea and vomiting.

The researchers also gave some participants ketanserin, a drug that dampens the response of serotonin type-2A receptors, together with mescaline, and found that this decreased responses to high doses of mescaline, such as increased heart rate and blood pressure. The researchers concluded that mescaline, like psilocybin and other classic psychedelics, acts on serotonin type-2A receptors.

Research on psychedelic-assisted therapy is “at a crossroads,” write researchers Stacey B. Armstrong and Alan K. Davis in a Science editorial. Key issues in the field, they say, include more effective control conditions, the lack of diverse representation in clinical trials, and a lack of data on participants’ long-term outcomes. “For any of these to become a breakthrough therapy, the scientific and biomedical community needs to do a better job of building confidence about the data coming from these trials,” they write.

OpenAI founder Sam Altman is the latest tech bigwig making headlines about his psychedelic experiences. Business Insider reports that Altman “dabbled in psychedelics at Burning Man” but has also had experiences through guides. Altman was previously the board chairman for the psychedelics company Journey Colab.

Boston Magazine profiles Eliza Dushku Palandjian, an actor who had starring roles in Bring It On, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, and Dollhouse, and is now a trained psychedelic therapist — and one of the top donors to a Massachusetts ballot measure that proposes to create state-regulated psychedelic therapy centers.

This last item is not for the faint of heart: The MEGA Journal of Surgery details the case of a man who amputated his penis during a psilocybin trip, and its reattachment by surgeons. (Warning: this journal article contains graphic photographs you might not want to see.)

You’re all caught up! We’ll be back in your inbox on Monday with a new 5 Questions interview.

If you know anyone who might like the latest on psychedelics in their inbox, feel free to forward this to them, or click below.

Got tips? Email us at themicrodose@berkeley.edu.