Welcome back to The Microdose, an independent journalism newsletter brought to you by the U.C. Berkeley Center for the Science of Psychedelics.

This week, we’ll be reporting from the Psychedelic Science 2025 conference in Denver, Colorado.

I kicked off my Thursday with a panel called “The Home Stretch: Pivotal Trials and Preparing for Launch” featuring leaders from three of the bigger psychedelics companies: Cybin CEO Doug Drysdale, Compass CEO Kabir Nath, and former Lykos CEO-turned-board member Amy Emerson. Both Cybin and Compass are developing synthetic versions of psilocybin, and Cybin is developing a DMT analog as well. Lykos continues to seek FDA approval for MDMA after it initially rejected the company’s application last summer. Compass has completed Phase III studies for its synthetic psilocybin COMP360, and Nath said they expected to announce results by the end of the month — but he did not give the crowd a preview of those results.

The group touched on a range of hot-button issues in clinical trials. One such topic was the role of therapy; in their clinical trials, both Cybin and Compass have touted their treatments’ lack of therapy. They do put clinicians in the room with clients for safety, but do not intervene or provide active intervention, and instead call it “psychological support” or “facilitation” — a model Rick Doblin criticized yesterday in his plenary speech without naming either company directly. Both Drysdale and Nath said it was not their job to dictate how clinicians should practice, and they emphasized that intervention could actually detract from clients’ experiences. Emerson added that the “therapy” portion of psychedelic-assisted therapy might look different depending on the drug and the indication it’s being used for; Nath gave the example of how people using psychedelics to treat anorexia may need more ongoing support than those receiving the same drug for depression.

The group also stressed the importance of not only setting the stage for psychedelic drugs to be prescribed, but also creating the infrastructure for them to be administered and to receive insurance reimbursements. They floated the idea that the process of getting psychedelic treatment might become similar to dialysis or Botox for migraines — a doctor prescribes it to a patient and educates them about what to expect before treatment, but clients go to a separate clinic for the actual treatment. If that does become the model, the panelists said psychedelic companies would need to collaborate to streamline training for clinicians or facilitators. In developing their clinical trials, these companies have been training staff on the use of their particular product for a particular medical indication, such as depression or anxiety, but that could quickly become unwieldy if a clinic aims to offer multiple treatment types with multiple drugs.

This was also the first session I’ve attended so far where the panelists have directly addressed the current administration’s potential role in advancing psychedelics. Emerson mentioned that “recent leadership changes” could lead to more changes in drug regulation. “There’s nothing to be unhappy about,” said Drysdale, who has publicly cheered members of the new administration for their support of psychedelics. The panelists also shouted out the American Psychiatric Association, which was also mentioned in MAPS board chair Vicky Dulai’s opening remarks yesterday alongside other VIPs, including Colorado Governor Jared Polis and former Texas Governor Rick Perry. “APA being here is an important signal,” said Nath.

On the policy track, legislative insiders discussed lessons learned from making state policy during a session titled “Drafting and Implementing Psychedelic Legislation.” Dave Kopilak, who drafted the ballot initiatives that led to the state-level legalizations of both cannabis and psilocybin in Oregon, said he much preferred the route of seeking legalization via ballot measures rather than state bills. Kopilak, who also worked with advocates in Washington state to draft a psilocybin bill, used that experience as an example of how bills can go awry: whereas ballot measures are “set in stone” upon submission to the state for consideration, bills are subject to amendments which can lead to power struggles between legislators and advocates, and can alter the legislation’s original aim. (After amendments, Washington’s bill was downgraded from full-on psilocybin services, similar to Oregon’s, to a proposal for the University of Washington to complete pilot research projects; ultimately, it did not pass.) “In the long run, ballot initiatives are the way to go if you want a well-functioning, non-medical wellness program in the next 10 years,” Kopilak said.

Other panelists, like political consultant Tamar Todd and Colorado Governor Jared Polis’s Special Advisor on Cannabis and Natural Medicine Ean Seeb, stressed the importance of building in flexibility to any proposed programs. Seeb mentioned that Colorado learned from Oregon’s psilocybin program and decided to create more types of facilitator licenses, and also did not allow local municipalities to ban psilocybin outright. Colorado’s ballot initiative also included other substances, including DMT and mescaline, but they aim to focus on developing access to ibogaine next. (In a speech yesterday, Colorado Governor Jared Polis also referenced this plan, as well as his recent moves to pardon people in the state who had been convicted of psilocybin-related offenses.)

Another policy panel titled “What Could the Next Iteration of a Psychedelic State Policy Look Like?” took stock of current state-by-state legislation and what direction it might move towards in the future. Attorney Barine Majewska said she had noticed a bias for “natural” psychedelics, rather than synthetic ones, and that she thought the growing conversation around ketamine’s risks might create further stigma for synthetic psychedelics. Attorney Allison Hoots pointed out that the barrier to creating state programs for lab-created psychedelics was the legal imperative to have all drug-related activity remain in state. In-state labs with the capacity to synthesize these drugs are likely to already be registered with the DEA, and they may be reluctant to synthesize a federally illegal drug for any state program, lest that cost them their DEA license. Psilocybin, on the other hand, can be easily grown outside labs.

Panelists also noted that state legislation had largely moved away from efforts to decriminalize psychedelics. Hoots raised concerns that this actually makes psychedelic use less safe by forcing it underground. Majewska advocated for Colorado’s system, which has two prongs: decriminalization in addition to a state-regulated program.

As far as lessons learned, Jared Moffat, policy director of psychedelics-focused political action committee New Approach, said that recent developments in Oregon have shown that perhaps there needs to be more flexibility built into regulations that only allow sessions to take place within service centers. (Currently, licensed facilitators are pushing for the right to administer psilocybin to terminally ill patients at hospice locations or homes.) Majewska advocated for the need for more conversation about reporting bad actors in psychedelics spaces. “There are enough bad actors to sink the entire movement,” she said. “There has to be some centralized way that we track them, report them, investigate them.”

Lone Star state psychedelic exceptionalism was on full display at the keynote address given by former Texas Governor Rick Perry. “That is going to change the world we live in,” Perry told the crowd in reference to a law signed into law last week in Texas that will invest $50 million into research on ibogaine. “This was a moment that people will look back on in a decade and say I know where I was when that legislation was passed,” Perry said. He acknowledged that his role as a proponent of psychedelics was not always popular with some in his conservative Republican crowd. When he began getting interested in psychedelics advocacy a longtime political consultant called him to say he was wasting his 40 years of conservative political clout on “that hippie sh*t.” But Perry said he ignored the warning. “I’m going to be engaged in this for the rest of my life,” he said.

During the panel “Between Ecstasy and Escapism: Raving as a Contemporary Ritual,” moderator and drug journalist Michelle Lhooq opened the question and answer period by saying, “Ask us if ketamine is killing the dance floor!” And when an audience member asked about addiction potential with drugs in the recreational space Lhooq jumped in to answer. “Ketamine is huge in the dance scene right now,” she said. “With demonstrably negative effects– it's dissociative and not community-minded.” But the blame for that uptick, she said, is not on the rave scene but on the medical community pushing ketamine as a panacea.

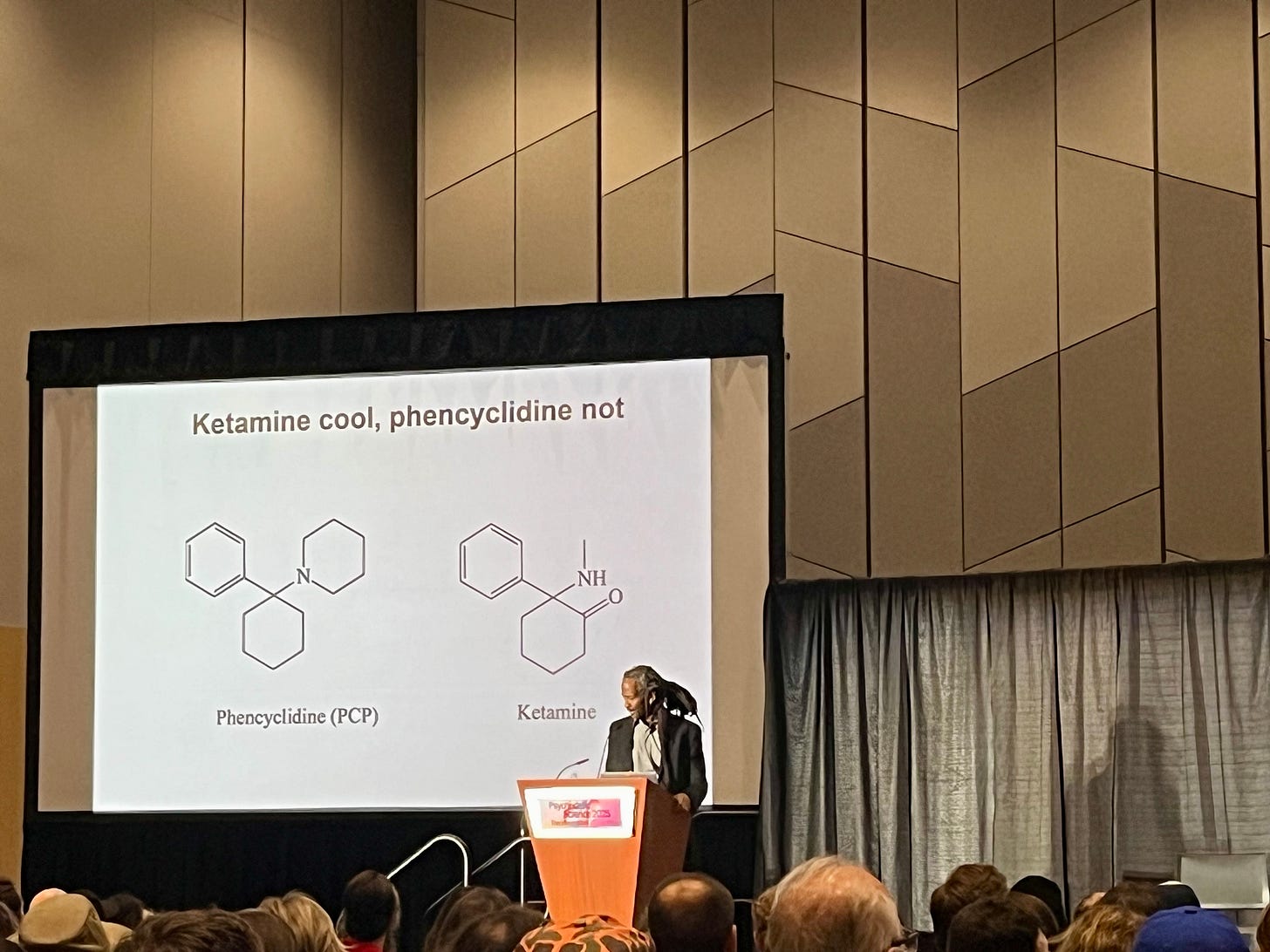

During a keynote speech by Carl Hart, Chair of the Department of Psychology at Columbia University, titled “Psychedelic exceptionalism is killing us,” Hart showed slides of different drug molecules side by side to illustrate that, for example, ketamine is not so different from PCP and yet one is an approved medication and the other is a demonized street drug. He said the total number of drug arrests in the last few decades has not changed but people are now being arrested for methamphetamine rather than cannabis because cannabis has become an industry dominated by white men in suits. He referenced a paper he authored in the journal Neuron titled “Exaggerating Harmful Drug Effects on the Brain is Killing Black People.” “Psychedelic exceptionalism is unwarranted and dangerous,” Hart told the assembled crowd.

The 400-capacity ballroom hosting “Love & Psychedelics: From Intimacy to Break Ups” was at overflow capacity with dozens of people waiting for a chance to squeeze in at the entrance. The panel included Richard Schwartz, who developed the model of psychotherapy called Internal Family Systems (IFS) as well as a researcher, a therapist and a life coach who work with couples. At the exit only door a harried-looking volunteer tried to prevent eager, would-be audience members from sneaking in. “I need to be in there,” one man begged.

The Microdose is here on the ground in Denver and will publish another dispatch with closing thoughts on Friday. The Microdose editor Malia Wollan is contributing reporting on the ground this week too.