Psychedelic science comics: 5 Questions for artist and cartoonist Audra McNamee

McNamee discusses how she made a psilocybin comic, and the role art can play in communicating complicated science to the public.

As an undergraduate at the University of Oregon, Audra McNamee was studying computer science, but when she heard about an opportunity to practice art, she jumped at it. The school’s Science and Comics Initiative paired up undergraduates with university scientists to create comics, and McNamee teamed up with neuroscientist Luca Mazzucato to create McNamee’s first comic, an eight-page spread about serotonin’s effects on the brain.

Soon after, Mazzucato and McNamee collaborated on a comic about Oregon’s Psilocybin Services program, and the two are now working on a book together. McNamee helps run the Science and Comics Initiative and works in the Mazzucato lab part-time making comics and doing science outreach, in addition to being a freelance artist. The Microdose spoke with McNamee about how she made her psilocybin comic, and the role art can play in communicating complicated science to the public.

Why use comics as a medium to explain science?

Science is inherently visual. If you're talking about a cell, it's nice to have a diagram of it; if you're talking about experimental results, you can bring in charts and graphs. So science communication in a visual medium already feels like a really natural fit. I think comics especially have a sneaky ability to get really deep and dense and technical and your reader isn't going to expect that, because comics have been stereotyped as frivolous, a kid thing. That’s certainly changing, but that's like a superpower of comics: to get at something that maybe someone would otherwise think was boring, or they thought they weren't smart enough to understand.

You collaborated with neuroscientist Luca Mazzucato to make these. How do researchers support this kind of work?

With grants from federal agencies like the National Science Foundation, there are often requirements for “broader impacts” that show the research benefits society. My science comics outreach work is part of the broader impact of the work supported by these grants.

How did you get the idea to make this psilocybin comic?

I’d been brought in to make comics, and had been working on some about the history and neuroscience of psychedelics right around the time that Measure 109 passed. [Reporter’s note: Measure 109 was the 2020 Oregon ballot initiative that established Oregon’s psilocybin services program.] After that I just had to find out as much as I possibly could about that — what was even going to happen in Oregon? When voters tell the state to build the first state-regulated psilocybin program, what does that even look like? Who is consulted?

What was your process for gathering information and creating the comic?

Luca totally supported me as I tried to figure this out, and it was a really cool collaboration; he provided a lot of the text about science and research. But we knew we weren't experts on everything, so we went out and interviewed basically anyone who was willing to talk to us. It was super cool because I got to see scientific collaborations starting; Luca and these other scientists would find how their work corresponds, what questions they're both thinking about For instance, we reached out to Jessie Uehling, who was a mycologist on the Oregon Psilocybin Services Advisory Board. She works at Oregon State University, which is just down the road from the University of Oregon. A quote from her became part of the prologue of the comic.

We also reached out to researchers at Oregon Health and Science University. We got to talk to a lot of the people and especially the scientists who were shaping the rules for Oregon’s program shortly after the advisory board had given the state their recommendations, and they were all generous with their time. We also reached out to Angie Allbee, who works for Psilocybin Services, who was also very generous with her time; after we had the whole thing laid out, she went through the comics on a super granular level and made sure that we weren't saying anything that was wrong. So I feel very confident in the information that's in the comic.

What are you thinking about as you design a comic — what’s the balance between the words and images?

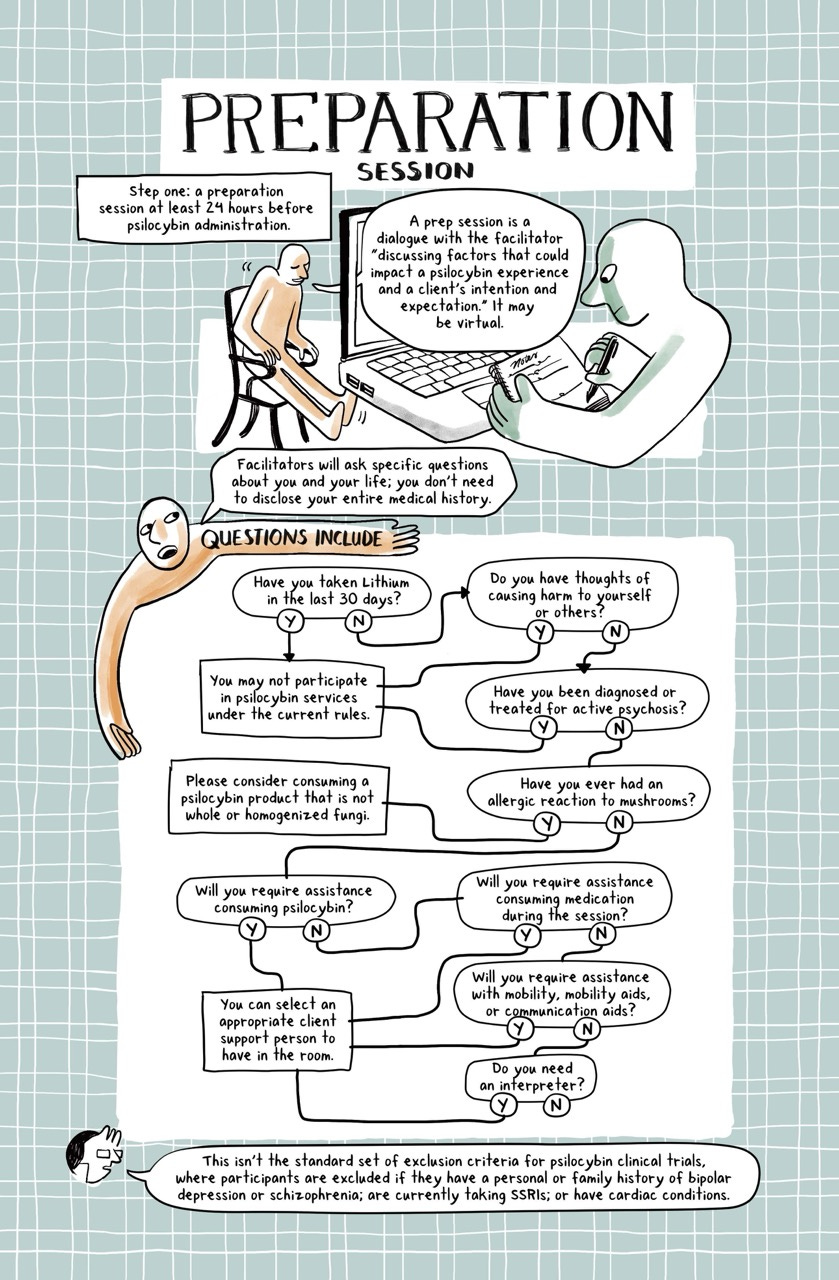

I always want the text of the comic to be supported by the visuals, but I never want them to be saying exactly the same thing. Because at that point, why even draw anything — it would just be a very slow article. So I want to figure out how to make as much of the information visual as I can while keeping the message clear.

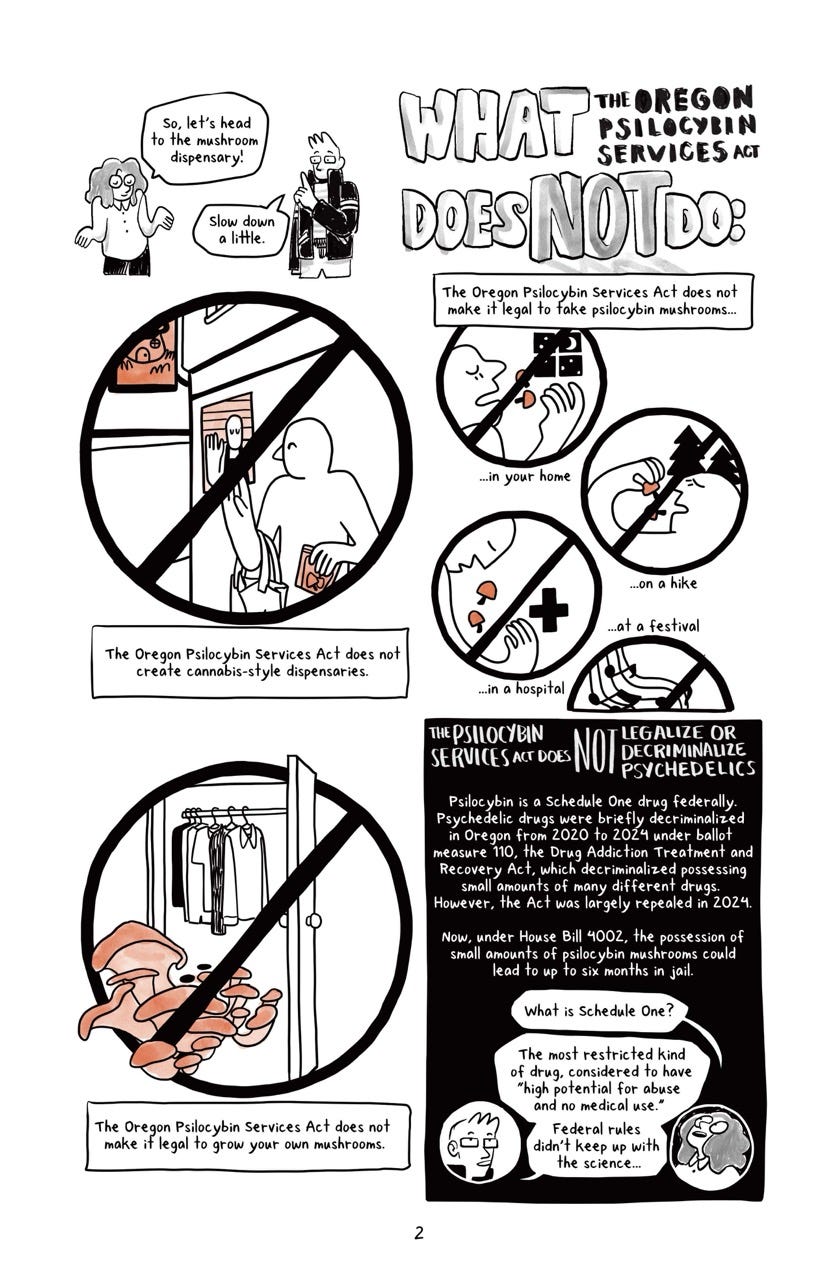

I also want to make sure that the text and images are conveying some sort of emotional story. I want the images to be playful and gripping, but not confusing. But all the while I’m also trying to fit in as much information as I can into the images that the reader might be unpacking consciously, like colors. For instance, in the psilocybin comic, I purposely made the psilocybin mushrooms an orange color. I also used color to draw a distinction between the facilitators — orange — and a facility, which was green. I like to keep my color and design choices as consistent as I can over the course of the comic so that even if something's not labeled, you can still infer who a character is.

My goal with this project was bringing in a lot of different people's perspectives so that a reader who doesn't know much about psychedelics gets a sense of what conversations are happening in this space. But I also wanted to be very specific about misconceptions or miscommunication, like about what the program does not do. That page was very simple design-wise — it's just like floating backgrounds, a couple of people's faces, the ballot measure — but it puts the focus on addressing this pretty big potential point of confusion.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity and length.