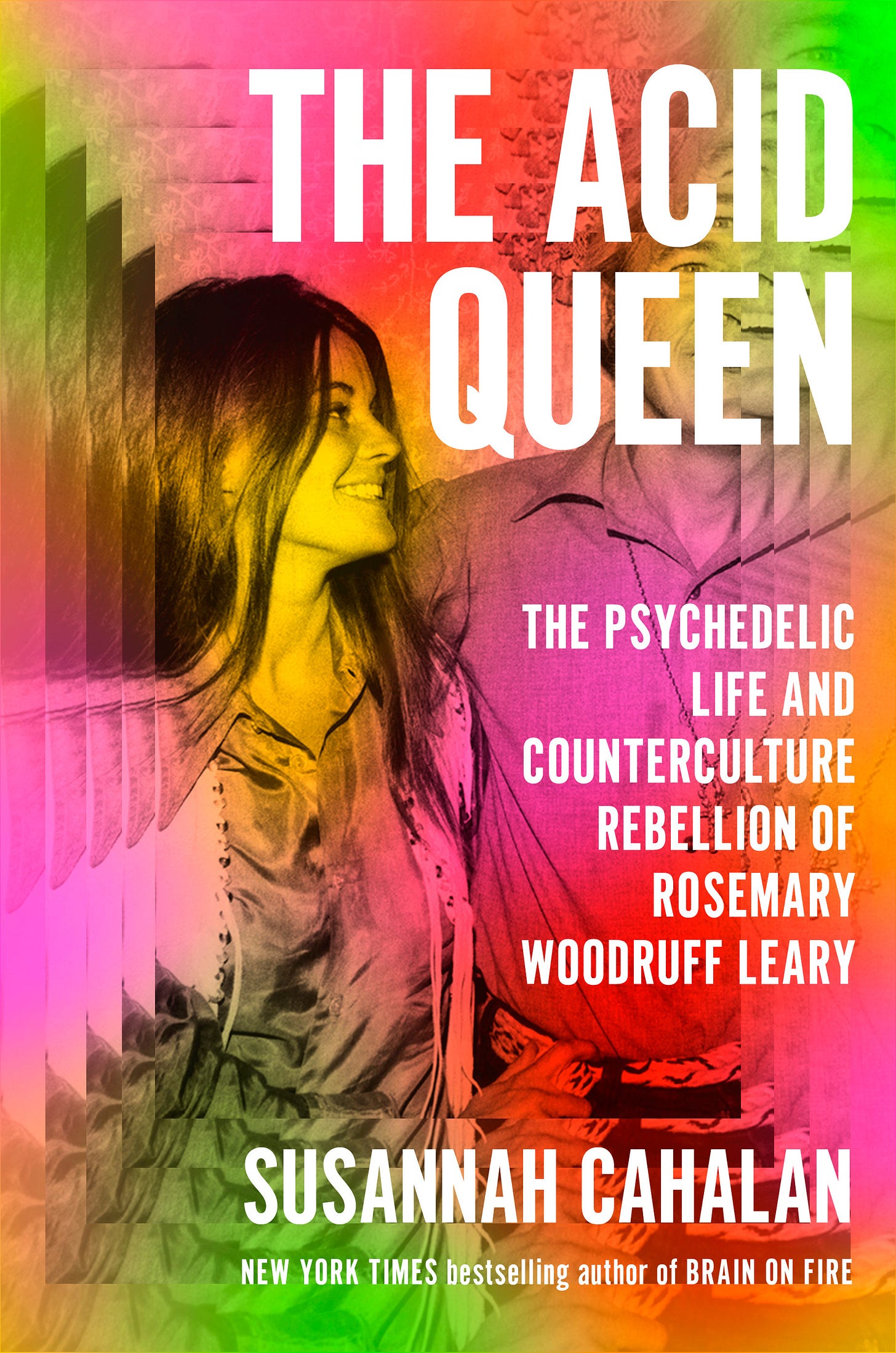

The Acid Queen

The Psychedelic Life and Counterculture Rebellion of Rosemary Woodruff Leary

Below is an excerpt from my book The Acid Queen: The Psychedelic Life and Counterculture Rebellion of Rosemary Woodruff Leary a biography of an important but largely forgotten figure in the psychedelic underground. Rosemary Woodruff Leary was married to psychologist Timothy Leary from 1967 to 1972, during the height of his notoriety. She edited his books and speeches and crafted some of his most enduring catchphrases, including his 1969 campaign slogan during his run for governor of California “Come Together, Join the Party,” which later inspired a #1 Beatles hit. She worked with the Weather Underground to orchestrate Leary’s escape from prison in 1970 and their asylum with the Black Panthers in Algeria, forcing her into the shadows for a quarter of a century for her refusal to turn on her friends and co-conspirators. Yet her role and self-sacrifice remain unacknowledged. She is an afterthought, a footnote in the Leary mythology. This is a wrong that I seek to right with this biography.

In this excerpt, I have focused on Timothy and Rosemary’s time together at the Hitchcock Estate in Millbrook, New York, a psychedelic commune that became the spiritual headquarters of the psychedelic revolution. Rosemary moved into the estate in 1965 and under Timothy’s guidance became the “queen of setting”—equal parts caretaker, trip guide, seductress, and seeker. This chapter explores Rosemary’s transformation from a peripheral character into the magnetic center of the Millbrook experiment.

Rosemary and Timothy grew to love each other in that brief five-month span when the overgrown vibrancy of late summer 1965 withered into the early days of winter—“a space between wars,” as she called that period. After Timothy paused the weekend workshops, most of the estate’s characters departed for more raucous shores in India or California, leaving Rosemary and Timothy more or less alone to settle into an easy rhythm of domestic bliss.

She let her hair grow long and sewed her own clothing, wearing smock dresses cut from fabric she found in the communal clothing heap. She made items for Timothy, too, and helped style him during his appearances, replacing tweeds with breezy, unbuttoned linen shirts—if he wore a shirt at all.

Chores took up most of her days. She rode the lawn mower, trimmed the apple trees, gathered wood for the fire, and cooked the meals, feeling purposeful and engaged with the world around her, each night sinking into the deep, restorative sleep of the truly active.

Wandering the property alone—sometimes naked if she felt like it—she would howl at the moon with the estate’s dogs, Fang and Obie. “There was always the possibility of finding a lost cabin in the woods, a lost place. It was so full of magic,” she said. She was Eve before the apple. “Nature girl,” she called herself. She felt free and safe and alive.

She communed with the old-growth trees and received the vibrations of the cornfields. She looked younger now than when she had arrived with that black eye, as if all that time in Timothy’s bed had shaved years off. She felt like a teenager in love.

“My life is serene and quiet,” she wrote to her mother. And filled with genuine passion. “You are incapable of awkwardness,” Timothy wrote to Rosemary, describing how graceful she looked—even on the toilet. In the din of a crowded local restaurant, he told her, “I am so proud to be seen with you.”

The greater Millbrook community respected Timothy, calling him “doctor”; even as a former professor, the Ivy League pedigree still carried weight. Timothy and Rosemary would walk down Main Street, past the library, post office, haberdashery, and hardware store on their way to pick up The New York Times at the Corner News Store, where the owner, John Kading, treated Timothy like visiting royalty. “I didn’t think he was crazy. I thought he was working on something—like Einstein,” Kading said.

The starry-eyed couple whispered about starting a whole new life of white picket fences and babies. Timothy could find someone else to run the movement. Somewhere, a photo exists of Rosemary ironing clothes while Timothy sits at the piano playing “Let’s Fall in Love.” “Still the moments I remember best,” she said. “The quiet ones. Walking in tandem in Millbrook and having a dinner by the fire.”

“What a wonderful mother you will be,” Timothy would say. “What beautiful children we will have together.”

Despite his renegade reputation, Timothy—who had just turned forty-five—held many of the old-fashioned beliefs typical of his generation. “He was very autocratic, quite old-fashioned in his attitude to women. He expected that he stretched out his hand, someone would be there to put a glass in it. He wanted to be married in a true mashed-potato, pork-chop, dinner-on-the-table kind of way,” Rosemary said.

Their arrangement appealed to her, too. Though she was fifteen years younger than Timothy, she was still a generation older than many of the second-wave feminists. Rosemary found joy in taking over the duties of mother/wife/goddess—not only to Timothy but also to his sixteen-year-old son, Jack, who lived at Millbrook, attended high school in the community, and had already dipped his finger in the infamous LSD-laced mayonnaise jar before she had arrived.

Rosemary could barely believe the estate’s library. Books on tarot, astrology, ancient Greek and Roman myths, and philosophy called to her. Many of the titles were published by the Bollingen Foundation, a group founded by Peggy Hitchcock’s family and named after the psychoanalyst Carl Jung’s country home in Switzerland. She devoured as many books as the hours would allow. Timothy called her his “bookworm. My Wittgenstein schoolteacher.”

“She was the best-read person I ever knew,” he wrote.

Rosemary compared their astrological charts and found “unbelievable alchemy” between her sun in Taurus and his in Libra, their shared moons in Aquarius and ascendants in Sagittarius. “You both need to contribute to this relationship on an equal basis,” read one interpretation of their compatibility. “You need to feel free with one another.”

She shared a reverence for astrology with Jung, who wrote to his mentor Sigmund Freud in 1911, “I dare say that we shall one day discover in astrology a good deal of knowledge that has been intuitively projected into the heavens.”

Timothy didn’t wear a watch. And for now, that kind of immersion in the moment—based on the Taoist philosophy that “things can’t be made to happen”—felt like a warm embrace. To have his attentions, his buoyant optimism, all to herself was divine.

Rosemary attempted to put into words what it was like to be seduced by Timothy. “He was so graceful and so likable,” she wrote. “He reshaped the world according to his momentary vision, which surrounded me like a bower, all flowers and laughing children.”

She felt flattered by the affirmation of her own intellect—his assumptions that she had the knowledge to appreciate his insights, catch his jokes, and smirk at his wit. She did not feel that he thought of himself as superior to her because she had never graduated from high school. “I felt clever, graceful, chosen,” she wrote. “That I’d met my match.”

She wrote ecstatically to her mother: “I am living on a beautiful estate with friends, and I have never before enjoyed my life as much as I do now.” They laughed so much in those days. Rosemary’s one-liners, which seemed to incense the men she had loved before, thrilled him. He loved how surprised she seemed when he laughed. “You are the funniest girl in the world,” he wrote to her in a letter.

Their sex was richer, too. He resisted orgasm, and they would spend hours in bed together celebrating each other’s bodies based on the ancient Hindu and Buddhist sexual practice called tantra. A “polyphase orgasm,” he believed, could alter your consciousness like psychedelics—sexual ecstasy channeled to harness and project potency. They created their own love mudras together, yogic hand gestures meant to empower. Timothy would later write that he based his tantra poem in Psychedelic Prayers on the time when he and Rosemary disappeared from a group to have sex outside:

Can you, murmuring

Lose all...

Fusing

Rosemary was not “turned on,” as in introduced to LSD, by Timothy, but he became her guide for their weekly sessions with acid—a kind of acidhead Pygmalion who would shape her as his hunk of marble with the lessons he learned from three hundred or so trips.

Crucially, Timothy gave her a container for the ecstatic. She had learned during her first peyote experience that it was not fulfilling to do it on a whim without knowledge. Allen Eager and the acid gypsies were wandering around in the dark, addicts looking for more oblivion. But Rosemary was different. She was looking for a vocation.

She learned that LSD was not merely a vehicle for spiritual transcendence, but a key evolutionary touchstone for humanity—one of the most important discoveries of the century, up there with the creation of the atomic bomb. For the first time in human history, Timothy told Rosemary, humans were harnessing the power of their nervous systems. You could commune with your cells, ride your DNA back in time to the one-celled creatures in the primordial soup, travel to different dimensions, and jet forth into the supersonic future.

So many people struggled to find the words to communicate these discoveries, but Timothy somehow managed to grow more clear-eyed, even self-possessed, when high. “He had that glorious thing that so many acid takers wish they could have, and that is to be able to do what they want with the drug; he was in absolute control,” a friend said.

Rosemary described life under his tutelage: “We were playing with Buddhism, Hinduism. We looked for revelations.” He showed her the beauty of insignificance. “The fact of the matter is that all apparent forms of matter and body are momentary clusters of energy. We are little more than flickers on a multidimensional television screen,” he wrote in The Psychedelic Experience. “This realization, directly experienced, can be delightful. You suddenly wake up from the delusion of separate form and hook up to the cosmic dance.” But he was also wise enough to warn her about the horror embedded in this knowledge. “The terror comes with the discovery of transience. Nothing is fixed, no form solid... Distrust.”

Rosemary proved to be a bright and willing apprentice. She learned how to prepare her body with clean food and meditation. They started a daily hatha yoga practice, thanks to Aldous Huxley’s recommendation that Timothy read Mircea Eliade’s book Yoga, which described the act of “integration or union”—that could, along with acid, help achieve the godhead.

With a mind slowed and receptive, revelations—messages from another realm—could be spotted everywhere. Stray birdsong at the right moment, the burst of a lightbulb, the crackling of a flame, something lost and found—it all had meaning. Self and universe had collided. This state of being, as understood by Jung’s theory of synchronicity, represented an embracing of the wisdom of the unconscious. It could make you feel connected, superior, or even paranoid and psychotic, depending on your disposition and environment. Rosemary experienced all of these states, though the dominant feeling was of true belief.

This training helped make Rosemary into the queen of “setting”; her warm and comforting demeanor grounded those in the throes of even the most challenging trips. She was a natural high priestess, a position she had learned as the perfect host back in New York with her second husband. She intuitively sensed what grounding foods to make, what kinds of bright but comforting colors to drape in cloth around the room, and where to place the candles. She knew what to say when things went sideways, and when to stay silent as someone traversed their visions alone.

There were few known female psychonauts to follow for this kind of training. Women were confidantes, calming tethers for the men to embark on frightening journeys into the psychic unknown, and they often wrote themselves out of psychedelic history due to fear of stigma and reproach. Thus, their names rarely made the record.

Rosemary, however, logged her trips—often in handwriting too blasted out to be legible—for posterity: “My new game should be easy. Love, warmth, comfort. My mind cannot be caught by the death fantasy. It is still there but faint, obscured by good feeling.” This theme of suicidality—not merely death and rebirth, but obliteration of herself—reoccurs. But her dark musings end with a list, as if interrupted mid-thought: “roast pork and carrots, fennel–thyme, fresh asparagus with hollandaise, and a green, green garlic salad.” Even while gazing into the abyss, Rosemary thought of feeding her lover.

“I aspire to be a radical intuitor,” she wrote—a person who valued learning over wealth, even food. She felt that Timothy had invited her into a “bubble of specialness.” And Rosemary bought into her own exceptionalism, during a time when her alternatives out there in the real world—where she was a high school dropout, fleeing yet another abusive relationship with a man addicted to heroin—were limited. She and Timothy sought liberation, or moksha, “release from the finitude that restricts us from limitless being, consciousness, and bliss,” as religion scholar and Harvard Psilocybin Project researcher Huston Smith wrote. Together, they strove to slough off the ego, destroy it even—much like the Buddhist idea of transcendence—while still honoring the body’s hedonic need for pleasure. They considered themselves to be like the Buddhists’ “Awakened Ones” and Gurdjieff’s chosen few with open eyes—those who had truly shaken off the slumber that stifled humankind. It sounds self-aggrandizing, and it was, but it was also pure. Rosemary truly believed.

She summed up the goal of all this internal work on a piece of scrap paper: “The sense of not existing—it wasn’t about LSD changing the world—it was about work to change oneself into a god-intoxicated being.” God was inside her, was her, was everywhere. Timothy honored the god inside Rosemary, just as she honored the god inside him, and so the guru–follower relationship didn’t flow just one way.

“Rosemary—sophisticated, worldly—continually joked me out of the trap of YMCA Hinduism, the goal of which was to become a Holy Man, a prospect she found too amusing for words,” Timothy wrote in Flashbacks. Rosemary provided a rare quality of authenticity, which was an antidote to Timothy’s professorial self-seriousness. She had spent hours in smoky bars with dangerous men. She knew about poverty, about suffering. And because she knew so much more than he did about real life, she felt comfortable poking holes in his inflated ego, pulling him—in a slightly reduced but far more palatable form—back down to earth. She adored him most when he embraced his innate silliness, like the time he discovered a straw hat and a cane in an abandoned trunk. Immediately he started “doing an elegant ‘Shuffle Off to Buffalo.’ He was a song-and-dance man, and he knew it.” The most important part was that she knew it, too.

Rosemary had so much to teach Timothy. “He had a deliberate naïveté, he wanted to be taught, to be instructed,” she said. She shared with him her love of science fiction—especially The Lord of the Rings series and The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch by Philip K. Dick—which Timothy later called “a profound contribution to my education.” Reading Rosemary’s books together altered the content of their psychedelic visions and would inspire Timothy Leary’s futurist philosophies—and some of his most out-there beliefs. “Through Rosemary I learned a critically important lesson: that the psychedelic experience could not only illuminate the theological concepts of the past but, more important, could map new visions.”

As a break from all this vision mapping, Rosemary periodically invited Timothy back into her old life in New York City. Over steak and scotch at Rolfe’s Chop House in the Financial District—where she had once gawked at the businessmen and held Charles’s hand in the back of David Amram’s car—Rosemary, so open now thanks to months of habitual acid use, unveiled herself.

“You told me the story of your life,” Timothy said of their dinner.

Did she speak about the backflips and tap dancing at the local bar with her father, or about her brief time in Hollywood, where she had played an extra in Operation Petticoat? Did she tell him about her second husband, how proud it made her to watch him caress the button accordion, how she had caught him cheating, how his betrayal had led her to seek out the erratic warmth of an alcoholic composer? Did she even mention her first husband? Not likely. She told few people about him—protecting herself even in this state of radical receptivity.

Whatever she relayed over dinner, Timothy listened without judgment. She felt that he truly heard her. His twinkling eyes danced around her face, urging her to make light of the suffering and to make humor out of the pain. “When all the tales I cared to tell were told, the past was banished,” she wrote.

He gave her a new way to frame the men from her past. They all—especially Charles and Allen—were holy men in search of something more meaningful than this reality. But they were looking in the wrong places. They used heroin and alcohol as “escape tickets” to envelop themselves in the “warm soft cocoon of nothingness.” They had chosen the wrong Door; she had chosen the right one.

That night he asked her to marry him. She said yes, but told him to keep it to themselves until his divorce from Nena was finalized.

She sat at the head of the table on Thanksgiving next to Timothy, serving thirty guests an elaborate meal of two turkeys, a ham, and a haunch of venison. That day they played a game of baseball, and she envisioned herself before her breasts grew in, rounding the bases at a field near her childhood home, when she felt she could run as fast as lightning. She had rediscovered that version of herself, the girl who would dance outside and wash her hair in thunderstorms as her mother called for her to come in for dinner. Images from her youth returned to her, especially during her trips. The dank, hallucinatory quality of those Missouri summers, pulling tomatoes from the vines that surrounded her house, kissing boys by the mosquito- infested lake by her school, running through patches of poison ivy and never getting a rash.

Her life entered into a continuous loop— all happening at once, the portal of Millbrook combining all these versions of herself. No matter how bad it got down the road, these moments of divine grace would stay with her.

The superficiality of her life before became impossible.

Adapted excerpt from The Acid Queen: The Psychedelic Life and Counterculture Rebellion of Rosemary Woodruff Leary by Susannah Cahalan. Published by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Random House. Copyright 2025.